The promise of the rewrite is very sweet. I have collected evidence that the more authentic the labor put into rewriting your screenplay, the greater the reward, and the reward is high, for whatever lovely, wonderful moments you might have discovered in the frightening process of plowing through the first draft, those moments, those seeds, are only seeds, and they only fulfill their destiny as giant, involving scenes in the movie that screens before people. So if I shortcut my revision, I will miss the prize, pure and simple.

The process of rewriting is recreating. I need to make a contract with myself to make room in every moment of my writing for the imaginative magic of inspiration, that flash of brilliance which some call talent, the muse, God, or desperation, to deliver something that did not exist just a second before, but now lives forever, like a huge white rabbit suddenly from a hat. This usually happens when my fingers are on the keyboard and there’s white below from where I’m typing, and I have no idea where I’m going. Or if I have some idea, I don’t have the answer, but I trust and that’s it.

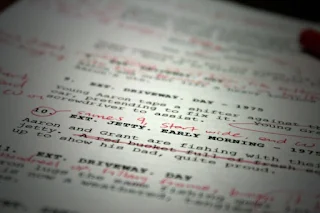

Rewriting is technically every change you make to your draft. There, I said it, so now you can’t come back and argue with me about what you think a rewrite is. But now I will tell you what rewriting really is, or what it really is not. Rewriting is not cutting and pasting. It’s not reading through your draft on your computer screen and changing words. It’s not pushing your cursor down the page, highlighting text and deleting it. I think this is called editing or deleting or garbage time or easy on the damn brain, but it’s not called rewriting over in the bust your ass capital of screenplay planet.

Rewriting is almost starting completely over. It’s almost accepting that you have nothing after celebrating like you won your tenth super bowl simply by typing the end and poking two brass fasteners through a pile of paper. Rewriting is taking that pile of paper, plopping it beside you where you can see it without a lot of movement of the head, and copying it over with an industrious attitude.

Okay, basically if you open a new file and name it second draft, or seventh, or whatever, lie all you want, but if you simply copy it over and the only thing that gets changed is the things that make you physically jerk in your chair, then you are not rewriting with an industrious attitude. An industrious attitude can mean a lot of things, I will probably call it something else next week, but it simply means you are open to work, and with a rewrite, the premise to work is the belief your script needs work. If you can’t see much wrong, how can it need a lot of work, and how is the rewrite going to work? It won’t. So make sure you have an open bent, and start typing it over.

image: http://www.bluecatscreenplay.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/rewriting_265x265.jpg

What happens? Well, if you’ve never done it, I’m not gonna tell you. A lot of screenwriters won’t even admit it they’ve never done it, because it breaks your neck. If you have done it, it’s almost time we did it again. Either way, go.

Now, how do I find out what’s broken? It’s not all on one page, and it’s hard to see the big picture of the awful thing. Well, this isn’t a book, this is just a short essay, so here’s a short list of tools to get yourself into and ready for your rewrite.

First, you got ask yourself, what’s the story, or more specifically, what are the stories? I usually make up a list of sentences that start with “The story of…” and fill in the blanks. What are the stories that are emerging from your current draft? What does your spirit want to tell versus what your poor brain thought you were going to do back in the coffee shop? You might find the list is long, and that’s a problem, too. There’s usually a main one, maybe one close behind, then a few tiny sweet ones. There is your family of stories. There they are. Now. How are you treating them?

This is where you can make some kind of a chart. Like a spreadsheet or something. Or the back of a dry cleaning receipt will do. Divide up your script into the beginning, act one, act two, act three, and the finish. By the way, I know there’s all sorts of act divisions. Modify my directions at your will. It’s fine. So within this chart you will pencil in the beats that exist within the current layout of your script. When you’re done charting the arcs of your family of stories, you will undoubtedly find HOLES. Wow. Nothing’s there. Didn’t see that before. Okay, you better put something in there.

Let’s say you got your chart pretty full, in fact, it looks like the stories of your movie have something resembling a beginning, middle and end. Now what you need is to make every scene as good as your best scene. Yeah, terrible news. How do you determine this? Grade your scenes. Some scenes might get an A. Others maybe a B. Give your work an F or two. Once you do this, you will know what scenes are functioning as placeholders and what are moneymakers. In the end, rewriting is making everything the most special ever. Anything short, and you have more rewriting to do. Unless you can live with an uneven ride. But this is a rewriting article, not a give up article.

Finally, a reminder. Screenwriting becomes artful when compression arrives. Shorten your everything. All dialogue and description is representative of this life traveled through a living soul. Uh, that’s you. A screenplay is just another poem, it’s just another small bit resembling something we recognize as human beings. Seven Samurai is a very short movie compared to what happens in a life, even shorter stacked against forever. But it lives beyond forever, doesn’t it?