The 'Grammar' of Television and Film

The 'Grammar' of Television and Film

Television and film use certain common conventions often referred to as the 'grammar' of these audiovisual media. This list includes some of the most important conventions for conveying meaning through particular camera and editing techniques (as well as some of the specialised vocabulary of film production).

Conventions aren't rules: expert practitioners break them for deliberate effect, which is one of the rare occasions that we become aware of what the convention is.

Camera Techniques: Distance and Angle

Images and text (c) 2001 Daniel Chandler - no unauthorized use - this image is watermarked

Long shot (LS). Shot which shows all or most of a fairly large subject (for example, a person) and usually much of the surroundings. Extreme Long Shot (ELS) - see establishing shot: In this type of shot the camera is at its furthest distance from the subject, emphasising the background. Medium Long Shot (MLS): In the case of a standing actor, the lower frame line cuts off his feet and ankles. Some documentaries with social themes favour keeping people in the longer shots, keeping social circumstances rather than the individual as the focus of attention.

Establishing shot. Opening shot or sequence, frequently an exterior 'General View' as an Extreme Long Shot (ELS). Used to set the scene.

Medium shots. Medium Shot or Mid-Shot (MS). In such a shot the subject or actor and its setting occupy roughly equal areas in the frame. In the case of the standing actor, the lower frame passes through the waist. There is space for hand gestures to be seen. Medium Close Shot (MCS): The setting can still be seen. The lower frame line passes through the chest of the actor. Medium shots are frequently used for the tight presentation of two actors (the two shot), or with dexterity three (the three shot).

Close-up (CU). A picture which shows a fairly small part of the scene, such as a character's face, in great detail so that it fills the screen. It abstracts the subject from a context. MCU (Medium Close-Up): head and shoulders. BCU (Big Close-Up): forehead to chin. Close-ups focus attention on a person's feelings or reactions, and are sometimes used in interviews to show people in a state of emotional excitement, grief or joy. In interviews, the use of BCUs may emphasise the interviewee's tension and suggest lying or guilt. BCUs are rarely used for important public figures; MCUs are preferred, the camera providing a sense of distance. Note that in western cultures the space within about 24 inches (60 cm) is generally felt to be private space, and BCUs may be invasive.

Images and text (c) 2001 Daniel Chandler - no unauthorized use - this image is watermarked

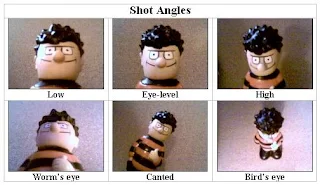

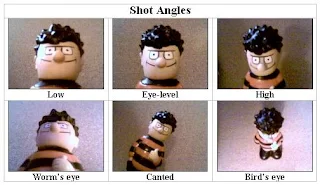

Angle of shot. The direction and height from which the camera takes the scene. The convention is that in 'factual' programmes subjects should be shot from eye-level only. In a high angle the camera looks down at a character, making the viewer feel more powerful than him or her, or suggesting an air of detachment. A low angle shot places camera below the character, exaggerating his or her importance. An overhead shot is one made from a position directly above the action.

Viewpoint. The apparent distance and angle from which the camera views and records the subject. Not to be confused with point-of-view shots or subjective camera shots.

Point-of-view shot (POV). A shot made from a camera position close to the line of sight of a performer who is to be watching the action shown in the point-of-view shot.

Two-shot. A shot of two people together.

Selective focus. Rendering only part of the action field in sharp focus through the use of a shallow depth of field. A shift of focus from foreground to background or vice versa is called rack focus.

Soft focus. An effect in which the sharpness of an image, or part of it, is reduced by the use of an optical device.

Wide-angle shot. A shot of a broad field of action taken with a wide-angle lens.

Tilted shot. When the camera is tilted on its axis so that normally vertical lines appear slanted to the left or right, ordinary expectations are frustrated. Such shots are often used in mystery and suspense films to create a sense of unease in the viewer.

Camera Techniques: Movement

Images and text (c) 2001 Daniel Chandler - no unauthorized use - this image is watermarked

Zoom. In zooming in the camera does not move; the lens is focussed down from a long-shot to a close-up whilst the picture is still being shown. The subject is magnified, and attention is concentrated on details previously invisible as the shot tightens (contrast tracking). It may be used to surprise the viewer. Zooming out reveals more of the scene (perhaps where a character is, or to whom he or she is speaking) as the shot widens. Zooming in rapidly brings not only the subject but also the background hurtling towards the viewer, which can be disconcerting. Zooming in and then out creates an ugly 'yo-yo' effect.

Following pan. The camera swivels (in the same base position) to follow a moving subject. A space is left in front of the subject: the pan 'leads' rather than 'trails'. A pan usually begins and ends with a few seconds of still picture to give greater impact. The speed of a pan across a subject creates a particular mood as well as establishing the viewer's relationship with the subject. 'Hosepiping' is continually panning across from one person to another; it looks clumsy.

Surveying pan. The camera slowly searches the scene: may build to a climax or anticlimax.

Tilt. A vertical movement of the camera - up or down- while the camera mounting stays fixed.

Crab. The camera moves (crabs) right or left.

Tracking (dollying). Tracking involves the camera itself being moved smoothly towards or away from the subject (contrast with zooming). Tracking in (like zooming) draws the viewer into a closer, more intense relationship with the subject; moving away tends to create emotional distance. Tracking back tends to divert attention to the edges of the screen. The speed of tracking may affect the viewer's mood. Rapid tracking (especially tracking in) is exciting; tracking back relaxes interest. In a dramatic narrative we may sometimes be drawn forward towards a subject against our will. Camera movement parallel to a moving subject permits speed without drawing attention to the camera itself.

Hand-held camera. A hand-held camera can produce a jerky, bouncy, unsteady image which may create a sense of immediacy or chaos. Its use is a form of subjective treatment.

Process shot. A shot made of action in front of a rear projection screen having on it still or moving images as a background.

Editing Techniques

Cut. Sudden change of shot from one viewpoint or location to another. On television cuts occur on average about every 7 or 8 seconds. Cutting may:

change the scene;

compress time;

vary the point of view; or

build up an image or idea.

There is always a reason for a cut, and you should ask yourself what the reason is. Less abrupt transitions are achieved with the fade, dissolve, and wipe

Matched cut. In a 'matched cut' a familiar relationship between the shots may make the change seem smooth:

continuity of direction;

completed action;*

a similar centre of attention in the frame;

a one-step change of shot size (e.g. long to medium);

a change of angle (conventionally at least 30 degrees).

*The cut is usually made on an action (for example, a person begins to turn towards a door in one shot; the next shot, taken from the doorway, catches him completing the turn). Because the viewer's eye is absorbed by the action he is unlikely to notice the movement of the cut itself.

Jump cut. Abrupt switch from one scene to another which may be used deliberately to make a dramatic point. Sometimes boldly used to begin or end action. Alternatively, it may be result of poor pictorial continuity, perhaps from deleting a section.

Motivated cut. Cut made just at the point where what has occurred makes the viewer immediately want to see something which is not currently visible (causing us, for instance, to accept compression of time). A typical feature is the shot/reverse shot technique (cuts coinciding with changes of speaker). Editing and camera work appear to be determined by the action. It is intimately associated with the 'privileged point of view' (see narrative style: objectivity).

Cutting rate. Frequent cuts may be used as deliberate interruptions to shock, surprise or emphasize.

Cutting rhythm. A cutting rhythm may be progressively shortened to increase tension. Cutting rhythm may create an exciting, lyrical or staccato effect in the viewer.

Cross-cut. A cut from one line of action to another. Also applied as an adjectuve to sequences which use such cuts.

Cutaway/cutaway shot (CA). A bridging, intercut shot between two shots of the same subject. It represents a secondary activity occurring at the same time as the main action. It may be preceded by a definite look or glance out of frame by a participant, or it may show something of which those in the preceding shot are unaware. (See narrative style: parallel development) It may be used to avoid the technical ugliness of a 'jump cut' where there would be uncomfortable jumps in time, place or viewpoint. It is often used to shortcut the passing of time.

Reaction shot. Any shot, usually a cutaway, in which a participant reacts to action which has just occurred.

Insert/insert shot. A bridging close-up shot inserted into the larger context, offering an essential detail of the scene (or a reshooting of the action with a different shot size or angle.)

Buffer shot (neutral shot). A bridging shot (normally taken with a separate camera) to separate two shots which would have reversed the continuity of direction.

Fade, dissolve (mix). Both fades and dissolves are gradual transitions between shots. In a fade the picture gradually appears from (fades in) or disappears to (fades out) a blank screen. A slow fade-in is a quiet introduction to a scene; a slow fade-out is a peaceful ending. Time lapses are often suggested by a slow fade-out and fade-in. A dissolve (or mix) involves fading out one picture while fading up another on top of it. The impression is of an image merging into and then becoming another. A slow mix usually suggests differences in time and place. Defocus or ripple dissolves are sometimes used to indicate flashbacks in time.

Superimpositions. Two of more images placed directly over each other (e.g. and eye and a camera lens to create a visual metaphor).

Wipe. An optical effect marking a transition between two shots. It appears to supplant an image by wiping it off the screen (as a line or in some complex pattern, such as by appearing to turn a page). The wipe is a technique which draws attention to itself and acts as a clear marker of change.

Inset. An inset is a special visual effect whereby a reduced shot is superimposed on the main shot. Often used to reveal a close-up detail of the main shot.

Split screen. The division of the screen into parts which can show the viewer several images at the same time (sometimes the same action from slightly different perspectives, sometimes similar actions at different times). This can convey the excitement and frenzy of certain activities, but it can also overload the viewer.

Stock shot. Footage already available and used for another purpose than the one for which it was originally filmed.

Invisible editing: See narrative style: continuity editing.

Manipulating Time

Screen time: a period of time represented by events within a film (e.g. a day, a week).

Subjective time. The time experienced or felt by a character in a film, as revealed through camera movement and editing (e.g. when a frightened person's flight from danger is prolonged).

Compressed time. The compression of time between sequences or scenes, and within scenes. This is the most frequent manipulation of time in films: it is achieved with cuts or dissolves. In a dramatic narative, if climbing a staircase is not a significant part of the plot, a shot of a character starting up the stairs may then cut to him entering a room. The logic of the situation and our past experience of medium tells us that the room is somewhere at the top of the stairs. Long journeys can be compressed into seconds. Time may also be compressed between cutaways in parallel editing. More subtle compression can occur after reaction shots or close-ups have intervened. The use of dissolves was once a cue for the passage of a relatively long period of time.

Long take. A single shot (or take, or run of the camera) which lasts for a relatively lengthy period of time. The long take has an 'authentic' feel since it is not inherently dramatic.

Simultaneous time. Events in different places can be presented as occurring at the same moment, by parallel editing or cross-cutting, by multiple images or split-screen. The conventional clue to indicate that events or shots are taking place at the same time is that there is no progression of shots: shots are either inserted into the main action or alternated with each other until the strands are somehow united.

Slow motion. Action which takes place on the screen at a slower rate than the rate at which the action took place before the camera. This is used: a) to make a fast action visible; b) to make a familiar action strange; c) to emphasise a dramatic moment. It can have a lyric and romantic quality or it can amplify violence.

Accelerated motion (undercranking) . This is used: a) to make a slow action visible; b) to make a familiar action funny; c) to increase the thrill of speed.

Reverse motion. Reproducing action backwards, for comic, magical or explanatory effect.

Replay. An action sequence repeated, often in slow motion, commonly featured in the filming of sport to review a significant event.

Freeze-frame. This gives the image the appearance of a still photograph. Clearly not a naturalistic device.

Flashback. A break in the chronology of a narrative in which events from the past are disclosed to the viewer. Formerly indicated conventionally with defocus or ripple dissolves.

Flashforward. Much less common than the flashback. Not normally associated with a particular character. Associated with objective treatments.

Extended or expanded time/overlapping action. The expansion of time can be accomplished by intercutting a series of shots, or by filming the action from different angles and editing them together. Part of an action may be repeated from another viewpoint, e.g. a character is shown from the inside of a building opening a door and the next shot, from the outside, shows him opening it again. Used nakedly this device disrupts the audience's sense of real time. The technique may be used unobtrusively to stretch time, perhaps to exaggerate, for dramatic effect, the time taken to walk down a corridor. Sometimes combined with slow motion.

Ambiguous time. Within the context of a well-defined time-scheme sequences may occur which are ambiguous in time. This is most frequently comunicated through dissolves and superimpositions.

Universal time. This is deliberately created to suggest universal relevance. Ideas rather than examples are emphasised. Context may be disrupted by frequent cuts and by the extensive use of close-ups and other shots which do not reveal a specific background.

Use of Sound

Direct sound. Live sound. This may have a sense of freshness, spontaneity and 'authentic' atmosphere, but it may not be acoustically ideal.

Studio sound. Sound recorded in the studio to improve the sound quality, eliminating unwanted background noise ('ambient sound'), e.g. dubbed dialogue. This may be then mixed with live environmental sound.

Selective sound. The removal of some sounds and the retention of others to make significant sounds more recognizable, or for dramatic effect - to create atmosphere, meaning and emotional nuance. Selective sound (and amplification) may make us aware of a watch or a bomb ticking. This can sometimes be a subjective device, leading us to identify with a character: to hear what he or she hears. Sound may be so selective that the lack of ambient sound can make it seem artificial or expressionistic.

Sound perspective/aural perspective. The impression of distance in sound, usually created through the use of selective sound. Note that even in live television a microphone is deliberately positioned, just as the camera is, and therefore may privilege certain participants.

Sound bridge. Adding to continuity through sound, by running sound (narration, dialogue or music) from one shot across a cut to another shot to make the action seem uninterrupted.

Dubbed dialogue. Post-recording the voice-track in the studio, the actors matching their words to the on-screen lip movements. Not confined to foreign-language dubbing.

Wildtrack (asynchronous sound). Sound which was self-evidently recorded separately from the visuals with which it is shown. For example, a studio voice-over added to a visual sequence later.

Parallel (synchronous) sound. Sound 'caused' by some event on screen, and which matches the action.

Commentary/voice-over narration. Commentary spoken off-screen over the shots shown. The voice-over can be used to:

introduce particular parts of a programme;

to add extra information not evident from the picture;

to interpret the images for the audience from a particular point of view;

to link parts of a sequence or programme together.

The commentary confers authority on a particular interpretation, particularly if the tone is moderate, assured and reasoned. In dramatic films, it may be the voice of one of the characters, unheard by the others.

Sound effects (SFX). Any sound from any source other than synchronised dialogue, narration or music. Dubbed-in sound effects can add to the illusion of reality: a stage- set door may gain from the addition of the sound of a heavy door slamming or creaking.

Music. Music helps to establish a sense of the pace of the accompanying scene. The rhythm of music usually dictates the rhythm of the cuts. The emotional colouring of the music also reinforces the mood of the scene. Background music is asynchronous music which accompanies a film. It is not normally intended to be noticeable. Conventionally, background music accelerates for a chase sequence, becomes louder to underscore a dramatically important action. Through repetition it can also link shots, scenes and sequences. Foreground music is often synchronous music which finds its source within the screen events (e.g. from a radio, TV, stereo or musicians in the scene). It may be a more credible and dramatically plausible way of bringing music into a programme than background music (a string orchestra sometimes seems bizarre in a Western).

Silence. The juxtaposition of an image and silence can frustrate expectations, provoke odd, self-conscious responses, intensify our attention, make us apprehensive, or make us feel dissociated from reality.

Lighting

Soft and harsh lighting. Soft and harsh lighting can manipulate a viewer's attitude towards a setting or a character. The way light is used can make objects, people and environments look beautiful or ugly, soft or harsh, artificial or real. Light may be used expressively or realitically.

Backlighting. A romantic heroine is often backlit to create a halo effect on her hair. Graphics

Text. Titles appear at or near the start of the programme. Their style - typeface, size, colour, background and pace - (together with music) can establish expectations about the atmosphere and style of the programme. Credits listing the main actors, the director, and so on, are normally shown at or near the beginning, whilst those listing the rest of the actors and programme makers are normally shown at the end. Some American narrative series begin with a lengthy pre-credit sequence. Credits are frequently superimposed on action or stills, and may be shown as a sequence of frames or scrolled up the screen. Captions are commonly used in news and documentaries to identify speakers, in documentaries, documentary dramas and dramatic naratives to indicate dates or locations. Subtitles at the bottom of the screen are usually used for translation or for the benefit of the hearing-impaired.

Graphics. Maps, graphs and diagrams are associated primarily with news, documentary and educational programmes.

Animation. Creating an illusion of movement, by inter-cutting stills, using graphics with movable sections, using step-by-step changes, or control wire activation.

Narrative style

Subjective treatment. The camera treatment is called 'subjective' when the viewer is treated as a participant (e.g. when the camera is addressed directly or when it imitates the viewpoint or movement of a character). We may be shown not only what a character sees, but how he or she sees it. A temporary 'first-person' use of camera as the character can be effective in conveying unusual states of mind or powerful experiences, such as dreaming, remembering, or moving very fast. If overused, it can draw too much attention to the camera. Moving the camera (or zooming) is a subjective camera effect, especially if the movement is not gradual or smooth.

Objective treatment. The 'objective point of view' involves treating the viewer as an observer. A major example is the 'privileged point of view' which involves watching from omniscient vantage points. Keeping the camera still whilst the subject moves towards or away from it is an objective camera effect.

Parallel development/parallel editing/cross-cutting. An intercut sequence of shots in which the camera shifts back and forth between one scene and another. Two distinct but related events seem to be happening at approximately the same time. A chase is a good example. Each scene serves as a cutaway for the other. Adds tension and excitement to dramatic action.

'Invisible editing'. This is the omniscient style of the realist feature films developed in Hollywood. The vast majority of narrative films are now edited in this way. The cuts are intended to be unobtrusive except for special dramatic shots. It supports rather than dominates the narrative: the story and the behaviour of its characters are the centre of attention. The technique gives the impression that the edits are always required are motivated by the events in the 'reality' that the camera is recording rather than the result of a desire to tell a story in a particular way. The 'seamlessness' convinces us of its 'realism', but its devices include:

the use of matched cuts (rather than jump cuts);

motivated cuts;

changes of shot through camera movement;

long takes;

the use of the sound bridge;

parallel development.

The editing isn't really 'invisible', but the conventions have become so familiar to visual literates that they no longer consciously notice them.

Mise-en-scene. (Contrast montage). 'Realistic' technique whereby meaning is conveyed through the relationship of things visible within a single shot (rather than, as with montage, the relationship between shots). An attempt is preserve space and time as much as possible; editing or fragmenting of scenes is minimised. Composition is therefore extremely important. The way people stand and move in relation to each other is important. Long shots and long takes are characteristic.

Montage/montage editing. In its broadest meaning, the process of cutting up film and editing it into the screened sequence. However, it may also be used to mean intellectual montage - the justaposition of short shots to represent action or ideas - or (especially in Hollywood), simply cutting between shots to condense a series of events. Intellectual montage is used to consciously convey subjective messages through the juxtaposition of shots which are related in composition or movement, through repetition of images, through cutting rhythm, detail or metaphor. Montage editing, unlike invisible editing, uses conspicuous techniques which may include: use of close- ups, relatively frequent cuts, dissolves, superimposition, fades and jump cuts. Such editing should suggest a particular meaning.

Talk to camera. The sight of a person looking ('full face') and talking directly at the camera establishes their authority or 'expert' status with the audience. Only certain people are normally allowed to do this, such as announcers, presenters, newsreaders, weather forecasters, interviewers, anchor-persons, and, on special occasions (e.g. ministerial broadcasts), key public figures. The words of 'ordinary' people are normally mediated by an interviewer. In a play or film talking to camera clearly breaks out of naturalistic conventions (the speaker may seem like an obtrusive narrator). A short sequence of this kind in a 'factual' programme is called a 'piece to camera'.

Tone. The mood or atmosphere of a programme (e.g. ironic, comic, nostalgic, romantic).

Formats and other features

Shot. A single run of the camera or the piece of film resulting from such a run.

Scene. A dramatic unit composed of a single or several shots. A scene usually takes place in a continuous time period, in the same setting, and involves the same characters.

Sequence. A dramatic unit composed of several scenes, all linked together by their emotional and narrative momentum.

Genre. Broad category of television or film programme. Genres include: soap operas, documentaries, game shows, 'cop shows' (police dramas), news programmes, 'chat' shows, phone-ins and sitcoms (situation comedies).

Series. A succession of programmes with a standard format.

Serial. An ongoing story in which each episode takes up where the last one left off. Soap operas are serials.

Talking heads. In some science programmes extensive use is made of interviews with a succession of specialists/ experts (the interviewer's questions having been edited out). This derogatively referred to as 'talking heads'. Speakers are sometimes allowed to talk to camera. The various interviews are sometimes cut together as if it were a debate, although the speakers are rarely in direct conversation.

Vox pop. Short for 'vox populi', Latin for 'voice of the people'. The same question is put to a range of people to give a flavour of 'what ordinary people think' about some issue. Answers are selected and edited together to achieve a rapid-fire stream of opinions.

Intertextuality. Intertextuality refers to relationships between different elements of a medium (e.g. formats and participants), and links with other media. One aspect of intertextuality is that programme participants who are known to the audience from other programmes bring with them images established in other contexts which effect the audience's perception of their current role. Another concerns issues arising from sandwiching advertisements between programmes on commercial television (young children, in particular, may make no clear distinction between them).

Further Reading

Arijon, Daniel (1976): Grammar of the Film Language. London: Focal Press

Bordwell, David & Kristin Thompson (1993): Film Art: An Introduction. New York: McGraw Hill

Izod, John (1984): Reading the Screen (York Handbooks). Harlow: Longman

Millerson, Gerald (1985): The Technique of Television Production. London: Focal Press

Monaco, James (1981): How to Read a Film. New York: Oxford University Press

Sobchack, Thomas and Vivian C Sobchack (1980): An Introduction to Film. Boston: Little, Brown and Company

Watts, Harris (1984): On Camera. London: BBC

Daniel Chandler

UWA 1994

This page has been accessed times since 18th September 1995.

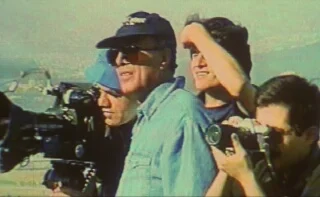

Director Abbas Kiarostami appearing as himself in the last scene of Taste of Cherry (Ta'm e Guilass, Iran, 1997)

Part 1: Basic Terms

Part 1: Basic Terms

AUTEUR

French for "author". Used by critics writing for Cahiers du cinema and other journals to indicate the figure, usually the director, who stamped a film with his/her own "personality". Opposed to "metteurs en scene" who merely transcribed a work achieved in another medium into film. The concept allowed critics to evaluate highly works of American genre cinema that were otherwise dismissed in favor of the developing European art cinema.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DIEGESIS

The diegesis includes objects, events, spaces and the characters that inhabit them, including things, actions, and attitudes not explicitly presented in the film but inferred by the audience. That audience constructs a diegetic world from the material presented in a narrative film. Some films make it impossible to construct a coherent diegetic world, for example Last Year at Marienbad (L'année dernière à Marienbad, Alan Resnais, 1961) or even contain no diegesis at all but deal only with the formal properties of film, for instance Mothlight (Stan Brakhage, 1963). The "diegetic world" of the documentary is usually taken to be simply the world, but some drama documentaries test that assumption such as Land Without Bread (Las Hurdes, Luis Buñuel, 1932).

Different media have different forms of diegesis. Henry V (Lawrence Olivier, England, 1944) starts with a long crane shot across a detailed model landscape of 16th century London. Over the course of its narrative, the film shifts its diegetic register from the presentational form of the Elizabethan theater to the representational form of mainstream narrative cinema.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

EDITING

The joining together of clips of film into a single filmstrip. The cut is a simple edit but there are many other possible ways to transition from one shot to another. See the section on editing.

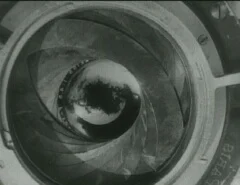

Picture: Yelizaveta Svilova at the editing table of Man with the Movie Camera (Chelovek s kinoapparatom, Dziga Vertov USSR, 1929) -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

FLASHBACK FLASHFORWARD

A jump backwards or forwards in diegetic time. With the use of flashback / flashforward the order of events in the plot no longer matches the order of events in the story. Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) is a famous film composed almost entirely of flashbacks and flashforwards. The film timeline spans over 60 years, as it traces the life of Charles Foster Kane from his childhood to his deathbed -- and on into the repercussions of his actions on the people around him. Some characters appear at several time periods in the film, usually being interviewed in the present and appearing in the past as they tell the reporter of their memories of Kane. Joseph Cotten, who plays Kane's best friend, is shown here as an old man in a rest home (with the help of some heavy make-up) and as a young man working with Kane in his newspaper.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FOCUS

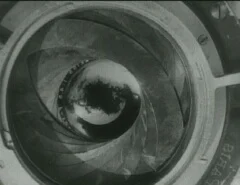

Focus refers to the degree to which light rays coming from any particular part of an object pass through the lens and reconverge at the same point on a frame of the film negative, creating sharp outlines and distinct textures that match the original object. This optical property of the cinema creates variations in depth of field -- through shallow focus, deep focus, and techniques such as racking focus. Dziga Vertov's films celebrated the power of cinema to create a "communist decoding of reality", most overtly in Man with the Movie Camera (Chelovek s kinoapparatom, USSR, 1929).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

GENRES

Types of film recognized by audiences and/or producers, sometimes retrospectively. These types are distinguished by narrative or stylistic conventions, or merely by their discursive organization in influential criticism. Genres are made necessary by high volume industrial production, for example in the mainstream cinema of the U.S.A and Japan.

Thriller/Detective film: The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941)

Horror film: Bride of Frankestein (John Whale, 1935)

Western: The Searchers (John Ford, 1956)

Musical: Singin' in the Rain (Stanley Donen, 1952)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MISE-EN-SCENE

All the things that are "put in the scene": the setting, the decor, the lighting, the costumes, the performance etc. Narrative films often manipulate the elements of mise-en-scene, such as decor, costume, and acting to intensify or undermine the ostensible significance of a particular scene.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

STORY / PLOT

Perhaps more correctly labelled fabula and syuzhet, story refers to all the audience infers about the events that occur in the diegesis on the basis of what they are shown by the plot -- the events that are directly presented in the film. The order, duration, and setting of those events, as well as the relation between them, all constitute elements of the plot. Story is always more extensive than plot even in the most straightforward drama but certain genres, such as the film noir and the thriller, manipulate the relationship of story and plot for dramatic purposes. A film such as Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000) forces its audience to continually reconstruct the story told in a temporally convoluted plot.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SCENE / SEQUENCE

A scene is a segment of a narrative film that usually takes place in a single time and place, often with the same characters. Sometimes a single scene may contain two lines of action, occurring in different spaces or even different times, that are related by means of crosscutting. Scene and sequence can usually be used interchangeably, though the latter term can also refer to a longer segment of film that does not obey the spatial and temporal unities of a single scene. For example, a montage sequence that shows in a few shots a process that occurs over a period of time.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SHOT

A single stream of images, uninterrupted by editing. The shot can use a static or a mobile framing, a standard or a non-standard frame rate, but it must be continuous. The shot is one of the basic units of cinema yet has always been subject to manipulation, for example stop-motion cinematography or superimposition. In contemporary cinema, with the use of computer graphics and sequences built-up from a series of still frames (eg. The Matrix), the boundaries of the shot are increasingly being challenged.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Click here if the Table of Contents frame is not visible at the left side of your screen.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

URL: http://classes.yale.edu/film-analysis

Last Modified: August 27, 2002

Certifying Authority: Film Studies Program

Copyright © 2002 Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520