So You Want to Be aFilmmaker

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

.... Recognizing how independent films differ from studio pictures

..... Getting an overview of the filmmaking process

~ln is a powerful medium. With the right script under your arm and a r~taff of eager team players, you're about to begin an exciting ride. The

single most important thing that goes into making a successful filmmaker is

the passion to tell a story. And the best way to tell your stories is with pictures.

Filmmaking is visual storytelling in the form of shots that make up

scenes and scenes that eventually make up a complete film.

You have the power to affect people's emotions, make them see things

differently, help them discover new ideas, or just create an escape for them.

In a darkened theater, you have an audience's undivided attention. They're

yours - entertain them, move them, make them laugh, make them cry. You

can't find a more powerful medium to express yourself.

As a filmmaker, you have to decide what you enjoy doing most. Do you like

putting things together and making them happen? Then you'd probably make

a great producer. Do you like things just a certain way, can you envision things

as they should be, and do you love working with people? Then your calling

may be directing. Or do you love telling stories, and are you always jotting

down great ideas that come to you? If so, then writing screenplays may be for

you. You can be referred to as a "triple-threat" in filmmaking if you write, produce,

and direct. Having some understanding of what the other people on your

crew do - like the cinematographer, the producer, the editor, the dolly grip,

and the prop or wardrobe person - is important. Understanding what each

person on your team does will improve your working relationship with them

and, in the end, make a better film.

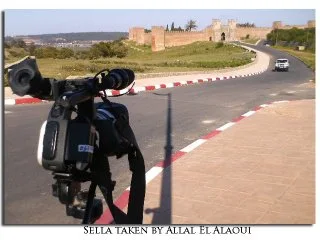

Digital filmmaking: The future of making films

+

Today, you can shoot your film in several different

formats. You can choose analog video or

digitalvideo or use a completely differentformat

by shooting with atraditional film camera using

super-B or 16mm film, or the choice of studio

productions, 35mm motion-picture film stock.

In this age of digital technology, almost anyone

with a computer and video camera can make a

film. You can purchase (for around $3,500) or

rent a 24-frame progressive digital camcorder

(like the Panasonic AG-DVX-l 00 - see Chapter

10 for more on cameras) that emulates the look

of motion picture film, without incurring the cost

of expensive film stock and an expensive

motion-picture camera.

If you can't afford one of these dig ita I cameras,

you can purchase computer software that takes

a harsh video image shot with an inexpensive

home camcorder and softens it to look more like

it was shot with a motion-picture film camera.

Many new computers come preloaded with

free editing software. In Ch apter 16, I give you

tips on starting your very own digital-editing

studio. You can also find out more information

on the world of digita I filmmaking in Digital

Video For Dummies by Martin Doucette (published

by Wiley). You can uncover more camera

information in Chapter 10.

High Definition (HO) TVis anew technology that

takes the video image one step farther. The picture

is much sharper, richer, and closer to what

the human eye sees as opposed to what the

video camera shows you. Watching HD video is

like looking through a window - the picture

seems to breathe. The new HDdigital cinema

cameras (the ones used by George Lucasl combine

HD technology with the 24-frame progressive

technology to emulate a unique film-like

picture quality in an electronic environment,

without the use of physical film. Unfortunately,

HD digital is still expensive (much more costly

than using a regular digital camcorder); the

cameras are extremely expensive to purchase,

and daily or weekly rental rates are usually

beyond what the independent filmmaker can

afford. HD also requires special monitors and

viewing equipmentthat processes the high resolution

in this new technology, making this

medium too complicated and expensive to be

part of the independent filmmaker's equipment.

So where do you find the good ideas to turn into films? An idea starts in your

head like a tiny seed, and then it sprouts and begins to grow, eventually blossoming

into an original screenplay. Don't have that tiny seed of an idea just

yet? Turn to Chapter 3, where you develop strategies for finding ideas or taking

a story or book and turning it into a screenplay. In that chapter, I show you

how to option (have temporary ownership of) existing material, whether it's

someone's personal story or a novel that's already been published.

You have a story in you. If something is a curiosity, is constantly on your

mind, or is troubling you, write about it. See Chapter 3 for tips on turning

your idea into a feature-length script (at least 90 pages). You'll find yourself

answering many of your own questions - you may even solve your problem.

Best of all, you could very well end up with a screenplay.

Part I: Filmmaking and Storytelling _

Surfing sites for filmmakers

+

You can find avirtually unlimited number of Web

sites dealing with filmmaking and independent

films. Becoming a filmmaker includes plugging

yourself into informative outlets that help you be

more aware of the filmmaker's world. Here I list

six sites that may be helpful to you as a lowbudget

filmmaker:

yI The Internet Movie Database (www . i mdb .

com) is avaluable information source used

by Hollywood executives. It lists the credits

of film and TV professionals and anyone

who has made any type of mark in the

entertainment industry. It's helpful for doing

research or a background check on an

actor or filmmaker.

yI The Independent Feature Project (www .

i fp . 0 rg) is an effective way to get connected

right away to the world of independent

filmmaking.

yI In Hollywood (www.inhollywood.com)

is a research site updated weekly that

offers current information on film projects.

FinancinfJ Your Film:

Where's the MonelJ?

yI The Association of Independent Video and

Filmmakers (www . ai vf . 0 rg) is an organization

that (as the name suggests) supports

ind ependent filmmakers. At the Web

site, you can find subscription information

to The Independent (a magazine geared

toward the independent filmmaker), discounts

on film-related books, festival

updates, crew classified ads, and other

membership perks.

yI IndieTalk (www.indietalk.com) is a discussion

forum forfilmmakers. Here you can

post and read messages about screenwriting,

finding distribution, financing, and lots

of other topics. It's a great site for communicating

with other independentfilmmakers.

yI Amazon.com (www.amazon.coml, an

Internet store where you can purchase

movies and books, has a plethora of information

for the inde pendent filmmaker, from

films available for sale on VHS and DVD to

cross-referencing actors, directors, producers,

and all related movie memorabilia.

+

After you've turned your idea into a completed screenplay, you can't get it

made (produced into a film) unless you have the financing. In Chapter 5, I

give you some great tips on how to find investors and how to put together a

prospectus to attract them to fund your film. You also find out about other

money-saving ideas like bartering and product placement.

In Chapter 5, I even show you how to set up your own Web site to help raise

awareness for your film, attract investors, and eventually serve as a promotional

site for your completed film. Raising money isn't as difficult as it sounds

if you have a great story and an organized business plan. You can find investors

who are looking to put their money into a film for the excitement of being involved with a film and/or the possibility of making a profit. Even friends

and family are potential investors for your film - especially if your budget is

in the low-numbers range.

On a Budi}et: Schedulini} Your Shoot

Budgeting your film is a delicate process. Oftentimes, you budget your film

first (this is usually the case with independent low-budget films) by breaking

down elements into categories - such as crew, props, equipment, and so

on - the total amount you have to spend. Your costs will be determined by

how long you'll need to shoot your film (scheduling will determine how many

shoot days you'll have), because the length of your shoot will tell you how

long you need to have people on salary, how long you'll need to rent equipment

and locations, and so on.

When you know you can only afford to pay salaries for a three-week shoot,

you then have to schedule your film so that it can be shot in three weeks.

You schedule your film's shoot by breaking down the script into separate

elements (see Chapter 4) and deciding how many scenes and shots you can

shoot each day, so that everything is completed in the three weeks you have

to work with. An independent filmmaker doesn't usually have the luxury of

scheduling the film first (breaking it down into how many days it will take to

shoot) and then seeing how much it will cost. You also should have a budget

and even a possible schedule as ammunition to show a potential investor.

Plannini} Your Shoot~ Shootini} Your Plan

Planning your film includes envisioning your shots through storyboarding,

by sketching out rough diagrams of what your shots and angles will look like

(see Chapter 9). You can storyboard your films even if you don't consider

yourself an artist. Draw stick characters or use storyboard software, like

Storyboard Quick or the 3-D Storyboard Lite, which gives you a cast of

characters along with a library of props and locations.

+

You also need to plan where you'll shoot your film. You research where

you're going to film much like planning a trip - then make all the appropriate

arrangements like figuring out how you're going to get there and the type of

accommodations if it's out of town. Regardless of where you're shooting, you'll

need to sign an agreement with the location owner to make sure you have it

reserved for your shoot dates. Also, you'll have to choose whether to film at

a reallocation, on a sound stage, or in a virtual location that you conjure up

inside your computer.

Film feeling

Audiences experien ce distinct psychological

effects when looking at film or video. Film tends

to have a nostalgic feeling, like you're watching

something that has already happened. Video

elicits the feeling that it's happening right nowunfolding

before your eyes, like the news.

Many people love old movies, not just because

of the great storytelling, but because of the sentimental

feeling they get, especially with old

black-and-white films or even the color films of

the 1960s. Steven Spielberg made Schindler's

List in black and white to help convey both the

film as a past event and the dreariness of the

war. The medium on which you set your storywhether

it be actual film celluloid on which the

images are developed, videotape, or digital with

afilm-style look- has aspecific feel and effect

on your audience.

+

Hiring Your Cast ...

Your film crew becomes your extended family (although maybe a dysfunctional

one). You spend many days and nights together - through good and

bad times - so hiring people who are passionate about your project and willing

to put their all into it is important. You may have to defer salary to your

crew if you're working on a tight budget. (Find out how to do that and more

Acting is not as difficult as you may think. People are born natural actors and

play many parts on the stage of life. Everyone is constantly in front of an

audience - or performing monologues when alone. In Chapter 8, I lead you

step by step through the process of finding a great cast to bring your screenplay

to life. I also fill you in on acting secrets so that you can direct your

actors and get the best performances.

FitminfJ in the RifJht Direction

Making a film requires special equipment, like cranes (tall apparatuses on

which you place the camera for high shots), dollies (which are like giant skateboards

that you put the camera on for movement), camera systems, and so

on. Without the proper lighting, you'll leave your actors in the darkliterally.

Lighting can set a mood and enhance the entire look of your film.

In addition to seeing your actors, you need to be able to hear them as well.

This is where the art of sound comes in. Microphones need to be placed

close enough to the actor to get a good sound recording, but not too close

as to have the microphone creep into the shot. The skill of recording great

sound comes from the production sound mixer.

If you're taking on the task of directing, you'll become a figurehead to your

actors and crew. You'll need to know howto give your actors direction and

what it takes to bring the best performance out of them.

In terms of telling your story visually, you'll need to understand a little

about the camera. Much like driving a car, you don't need to understand how

it works, but you need to know how to drive it (your cinematographer should

be the expert with the camera and its internal operations). The camera is a

magical box that will capture images so that you can effectively and visually

tell your story to the world.

Seeint) the lit)

The eye of the camera needs adequate light to "see" a proper imagewhether

it be appropriate exposure for a film camera, or enough light to get

a proper light reading for a video camera. Chapter 11 gives you the lowdown

on lighting. Lighting can be very powerful and can affect the mood and tone

of every scene in your film. A great cinematographer combined with an efficient

gaffer (see Chapter 7) will ensure that your film has a great look.

Production sound is extremely important because your actors must be heard

correctly. Your sound mixer, who's in charge of primarily recording your

actors' dialogue on set, needs to know the right microphones and soundmixing

equipment to use, as you see in Chapter 12.

Actors takint) 'Jour direction

The director's job is to help the actors create believable performances in

front of the camera that lure the audience into your story and make them

care about your characters. Directing also involves guiding your actors to

move effectively within the confines of the camera frame. Chapter 13 guides

you in the right direction with some great secrets on how to warm up your

actors and prepare them to give their best on the set.

Threatening film

Chris Gore runs an e-mail newsletter called Film

Threat Magazine. If you're afilmmaker or want

to be afilmmaker, you need to be on this mailing

list. You'll find interesting reading including

information on film festivals, box office updates,

and brutally honest movie reviews, along with

actor and filmmaker interviews. Get more information

at www.filmthreat.com.

+

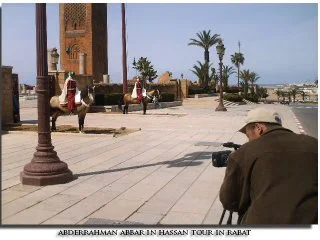

ShootinfJ throufJh the camera

Directing the camera requires some technical knowledge of how the

camera works and what each lens and filter does, which I explain in Chapter 10.

Chapter 14 addresses how to frame your shots and when to move the camera.

In that chapter, you also discover the skills that make up a successful director

and how to run a smooth, organized set.

Cut It Out!: EditinfJ Your Film

Editing your film gives you a chance to step back and look at the sequence of

events and all the available shot angles in order to shape and mold them into

the most effective production. You can even repair a bad film (or at least make

it better) during the editing process. Editing is the time when you'll really see

your film coming together. It's a fascinating phase of filmmaking and can be

very rewarding as you watch your baby come together piece by piece.

Nonlinear editing software is now available for virtually any computer (starting

at $50), and it allows you to edit anything from a home movie to a professional

theatrical-length piece (90 to 120 minutes). The technology of

nonlinear editing allows you to cut your shots together in virtually any order.

You can easily see different variations of cutting different shots together,

rearrange them, and move or delete in between scenes in a concise and easyto-

understand manner. Chapter 15 tells you what the new digital technology

makes available to you for editing your film on your desktop.

ListeninfJ to 'Jour film

At the editing stage, you add and create the audio, dialogue, sound effects,

and music as you see and "hear" in Chapter 16. Titles and credits are important,

too, and I discuss them in Chapter 18.

SimulatinfJ film with software

If you can't afford to shoot your movie on film, you can use a technology by

FilmLook (www. fi 1ml oak. com). FilmLook runs your video footage through

special processors, electronic settings, and so on, and creates the effect that

your image was shot on film.

Software programs can also make your video footage look more like film.

These programs emulate grain, softness, subtle flutter, and so on. Bullet software

available at www. redgi antsoftwa re. com can convert your harsh video

footage to look like it was shot on film. The video-to-film process converts 30frame

video to a 24-frame pulldown, adding elements to create the illusion

that your images were photographed on film as opposed to shot on video.

Using software that makes your video footage look like film takes time for the

computer to process. Depending on what software you use, the processing

time could take hours or days just to turn video footage into something that

looks more like film. With a 24-frame progressive video camera, you get the

film image immediately as you shoot. (See Chapter 10 for more information

on 24-frame progressive Video.)

DistributinfJ Your Film and

FindinfJ an Audience

The final, and probably most important, stage of making a film is distribution.

Without the proper distribution, your film may sit on a shelf and never be

experienced by an audience. Successful distribution can make the difference

between your film making $10 (the ticket your mother buys) or $100 million

at the box office. The Blair Witch Project may never have generated a dime

if it hadn't been discovered at the Sundance Film Festival by Artisan

Entertainment.

There's no business like ShowBiz Expo

+

ShowBiz Expo is one of my favorite conventions.

Four times ayear, Mind Ventures offers regional

conventions in Miami, Chicago, Los Angeles, and

New York. Thousands of people flock to the expo

to schmooze with fellow filmmakers, network,

and see the latest developments in equipment

technology (and in some cases, even experiment

with the technology, hands-on). It's like a giant

toy store forfilmmakers.

Even mediocre films have done well commercially because of successful distribution

tactics. And great films have flopped at the box office because the

distributor didn't carry out a successful distribution plan.

Here are several suggestions on how to find a distributor for your film:

~ Send out your screenplay before shooting your film and see if you can

get distribution interest based on the script.

~ Send out screening cassettes of your completed film to distributors with

the potential that one will acquire your film and distribute it.

~ Enter your finished film in film festivals like the Sundance Film Festival

(see Chapter 20) and let a distributor discover you.

~ Have a premiere screening for your film and invite distributors and

industry people to the big event.

~ Set up a publicity stunt (see Chapter 22) to attract the attention of a

distributor.

Check out Chapter 19 for more tips and secrets to finding a distributor.

+